Phantastica

Peyote (Sophophora williamsii)

S. williamsii, commonly known as peyote, is a cactus found in parts of the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico. The cactus consists of small, round flower-like bulbs, termed ‘buttons’, that grow in warm, arid climates, ranging in elevation from 330 ft. to 6200 ft. The cacti are commonly found on or around limestone hills. Its history is deeply rooted in Native American religious ceremonies, and has been linked to tribes such as the Chichimeca, Toltec, Tarahumara, Cora, Huichol, and more recently, the Kiowa and Comanche tribes of Texas and Oklahoma (Schultes, 1938; Erowid). Due to its widespread use among tribes of the region, it is likely that the different cultures throughout the southwest discovered the effects of peyote independently of one another.

Spanish conquerors were the first of the Europeans to discover its use in religious practice. Due to its Pagan roots and hallucinogenic qualities, the Spanish colonists attempted to suppress the use of peyote among the natives, chasing many ‘peyotists’ into hiding in the foothills. Its first official documentation by a European dates back to the 16th century A.D., when Sahagún noted, “It is white. It is found in the North Country. Those who eat or drink it see visions either frightful or laughable. This intoxication lasts two or three days and then ceases” (Erowid). His referral to the cactus as white is likely a reference peyote in its ground state. Archaeological discoveries have found evidence of peyote use as far back as 3780 B.C., while its ritualistic use dates back at least two thousand years (Seedi et al, 2005; Schultes, 1938). Currently, peyote is classified as a schedule I controlled substance by both the United States government. However, it is legally allowed for consumption during specified religious ceremonies of various Native American churches and religious groups.

Peyote is said to induce a hallucinogenic state: The user perceives minor changes and strange intoxication, followed by feelings of inner tranquility, oneness with life, heightened awareness, and rapid thought flow. As time continues, the effects of the peyote increase and become more visual, producing a stunning array of colors and geometric distortion in shapes. Eventually the effects wear off, while the user is not known to sustain any sort of crash, usually coming out of the experience relaxed and at peace with their self (Erowid). Though its vision inducing effects are the reason for its controversy and legal regulation, Richard Evans Schultes, one of the nation’s foremost botanists of the 20th century concluded that the motives for peyote’s use are more closely related to its therapeutic and stimulating properties. In fact, one account of a ceremony of the Cora tribe was noted to include a period of nonstop dancing lasting from five o’clock in the afternoon until seven o’clock the following morning, fueled by consumption of peyote ground up and consumed as a beverage (Erowid).

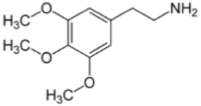

There are a variety of phenethylamines present in peyote, including hordenine, anhalonine, anhalonidine, pellotine, lophophorine, anhalamine, anhalinine, anhalidine, and last but not least, mescaline. Mescaline is the principal active ingredient in peyote responsible for its vision producing capabilities. A typical dose for a peyote user includes approximately 350mg pure mescaline, requiring the consumption of between 6 and 20 peyote buttons (Erowid; Schultes; Shulgin & Shulgin). Many of the Native Americans chew the dried buttons on their own, but there are other methods of consumption as well. These include boiling the buttons in water to produce a concentrated tea, and grinding up the dried buttons to produce a powder that can be fashioned into a beverage, placed into capsules, or infused anally (peyote has an extremely and sometimes unbearable bitter taste, and some users will go to great lengths to avoid the taste). However, it generally takes at least 20 of the capsules to obtain a typical dosage of mescaline (Erowid). Due to peyote’s voracity to the digestive tract, it is strongly suggested that users fast for at least six hours before peyote consumption.

Negative effects for long-term peyote use have not been significantly observed. In fact, in the Rand Mental Health Inventory, long-term peyote users showed better results over non-users in the “general positive affect” and “psychological well-being” categories (Halpern, 2005). Furthermore, peyote has been shown to have anti-microbial effects due to the biotic agent, hordenine. It has also been used by Native Americans to treat a variety of symptoms, including toothache, fever, breast-pain and pain from childbirth, skin diseases, diabetes, rheumatism, colds, and blindness (McCleary et al., 1960). There are a variety of negative short-term effects however, including nausea, vomiting, insomnia, paranoia, and similar symptoms. Visions are highly variable from person to person, and in some cases may be unpleasant or frightening. The negative symptoms generally increase with dose (Erowid).

References

El Seedi, H.R.; De Smet, P.A.; Beck, O.; Possnert, G.; Bruhn, J.G.; Prehistoric Peyote Use: Alkaloid Analysis and Radiocarbon Dating of Archaelogical Specimens of Lophophora from Texas. J. Ethnopharmacol., 2005, 101(3):238-242.

Erowid. Peyote. http://www.erowid.org/plants/peyote/peyote.shtml (accessed Feb 21, 2012).

Halpern, J.H. Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long-Term Peyote Use Among Native Americans. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005, 58:624-631.

McCleary, J.A.; Sypherd, P.S.: Walkington, D.L. Antibiotic Activity of an Extract of Peyote. Econ. Botany, 1960, 14: 247-249.

Schultes, R.E. The Appeal of Peyote (Lophophora Williamsii) as a Medicine. Amer. Anthropol. 1938, 40(4): 698-715.

Shulgin, A.; Shulgin, A. PIHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. Transform Press: Berkeley, 1991.

“The white man goes into his church house and talks about Jesus; the Indian goes into his teepee and talks to Jesus.” – J.S. Slotkin, author of The Peyote Religion

Thursday, February 23, 2012

Peyote - Collin Wulff