Phantastica

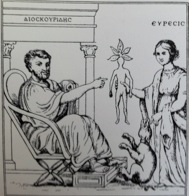

Mandragora officinarum, commonly known as the mandrake, has long been associated with the arts of healing, harming, and hexing, boasting a rich history of use throughout its indigenous territories bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Myths and folklore surrounding its use are endless and the plant has been referenced in numerous works and writings, ranging from the Bible to English literature to poetry from the Middle Ages. Its first scholarly documentation appears in an illustrated manuscript from the early 6th century, written by the Greek herbalist, Dioscorides, entitled the Juliana Anicia Codex. One specific illustration from this piece shows Dioscorides receiving the mandrake plant from Heuresis, the goddess of discovery, highlighting the belief that this plant was, indeed, that of the Gods.

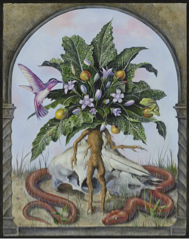

Interest in this herbaceous perennial was first sparked by the extraordinary resemblance its twisted and branched roots had to the human form. Greek Pythagoras of the 1st century described the root as an anthropomorph, meaning tiny human being, and early Christianity held the belief that the mandrake was originally created by God as an experiment before he created man (Shultes et al. 1998). As common with numerous medicinal plants and products, the root was also said to bear aphrodisiac properties and was frequently associated with Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love. The delightfully scented yellow fruit of the mandrake are often referred to as the Apples of Love and are identical to the golden apples of Aphrodite. It is even believed that it was this fruit of the mandrake that Eve so disobediently indulged in inside the Garden of Eden. The early 16th century philosophy known as the Doctrine of Signatures, first proposed by the alchemist, Paracelsus, preached that the appearance of a plant could predict its magical or medicinal properties (Mann 1992). It was this resemblance that led to the belief that the mandrake held great supernatural powers over the human mind and body and was often associated the enhancement of fertility, as referenced in the Bible.

While this plant was often employed to create life, it was used to destroy life as well. Fermented mandrake root was a favorite amongst poisoners of the Renaissance Age, as the induced trembling, stomach pains, and yellowing of the eyes inevitably ended in epileptic seizures and death (Mann 1992). The Monastic medicinal uses of mandrake first appeared around 1260 in the encyclopedic work of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, entitled, Liber de Propritatibus Rerum. It was reported that, “the rind thereof medled with wine… geve to them to drink that shall be cut in their body for they should slepe and not fele the sore knitting” (Mann 1992). Even more notorious than its use for murder and medicine is the mandrake’s association with magic. The plant was combined with Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade) and Hyoscyamus niger (henbane) to create a concoction famous for its use in soothsaying, sorcery, and supernatural communication, known as the Witches’ Brew. The addition of fats and oils allowed the mixture to penetrate through skin or be easily absorbed through sweat ducts and bodily orifices (Mann 1992). The use of these salves and ointments allowed the psychoactive constituents of the plants to gain access to the blood stream and brain without passing through the gut, running the risk of poisoning. There are several written accounts that report on the wild ‘flights of fancy’ experienced by these women, typically during ceremonies known as Sabbats. Consumption of this mixture induced vivid episodes of flying and orgiastic adventures, followed by hallucinations occurring during a transition from consciousness to narcosis (Shultes et al. 1998).

Despite common utilization for purposes of healing, harming, and hexing, the infamy of the mandrake undoubtedly lies with the superstitions surrounding its collection. Around the 3rd century, legends began to arise warning of the great caution required for the harvesting of this root and various Greek pharmacists and herbalist described curious precautions necessary for its extractions. Among the wildest include tracing a circle three times around the plant with a sword and then cutting it while facing west as well as keeping windward to avoid the foul stench of the harvested plant (Shultes et al. 1998). Perhaps the most famous of the superstitions, referenced in numerous works ranging from Shakespeare to Harry Potter, is that of the horrendous shrieks induced by the uprooting of the plant, said to be so unbearable they could drive the collector mad. It became common to use black dogs to remove the plant from the earth, tying one end of a rope around the dog’s neck and the other end to the plant, a practice often revealed in paintings and illustrations of the time.

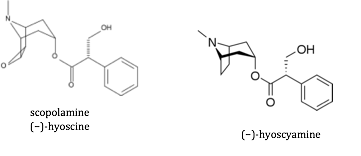

So what is it about the mandrake that is responsible for its notoriety as a plant of the gods? This plant, along with the other members of the family, Solanaceae, contains relatively high concentrations of tropane alkaloids, namely (−)-hyoscyamine and scopolamine, also known as (−)-hyoscine. It is generally only these enantiomerically pure alkaloids that are found in the raw plant material, however, hyoscyamine is much more easily racemized than hyoscine, and atropine, the third dominant tropane alkaloid found in mandrake, is simply its racemic form (Dewick 2009). The biological activity of the (+)- enantiomer is approximately 20-30 times less than that of the natural (−)-form, so it is not surprising that scopolamine, the main component of the mandrake, is, in fact, the compound responsible for the produced hallucinogenic effects. Upon entering the body, these alkaloids compete with acetylcholine for the muscarinic site of the parasympathetic nervous system, preventing the passage of nerve impulses (Dewick 2009). It is this inhibition and depressant activity that ultimately induces narcosis. As is characteristic of all tropane alkaloids, secretion from glands innervated by acetylcholine is prevented, resulting in reduced flow of saliva and mucus in the respiratory tract. It was these anti-secretory effects of scopolamine that first initiated its use as a medicine used prior to surgery. In more recent times, scopolamine has been utilized for its depressant action on the central nervous system, including antispasmodic action on the gastrointestinal tract and anti-emetic activity, employed as a sedative for motion sickness (Dewick 2009).

References

Dewick P. M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; Wiley: West Sussex, 2009.

Mann J. Murder, Magic, and Medicine; Oxford University: New York, 1992.

Shultes R. E., A. Hofmann, and C. Rätsch. Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers; Healing Arts: Rochester, 1998.

“The Mandrake is the ‘Tree of Knowledge’ and the burning love ignited by its pleasure is the origin of the human race.”

− Hugo Rahner

Greek Myths in Christian Meaning (1957)

Friday, February 17, 2012

Mandragora officinarium - Meghan Brady

“And Reuben went in the days of wheat harvest, and found mandrakes in the field, and brought them unto his mother Leah. Then Rachel said to Leah, Give me, I pray thee, of thy son's mandrakes.”

− Genesis 30:14

“shrieks like mandrakes, torn out of the earth,/ That living mortals, hearing them, run mad”

− Romeo and Juliet (IV, iii)

“Go, and catch a falling star, Get with child a mandrake root, Tell me, where all the past years are, Or who cleft the devil’s foot.”

− John Donne

“Then on the still night air, The bark of a dog is heard, A shriek! A groan! A human cry. A trumpet sound, The mandrake root lies captive on the ground.”

− Anonymous poem from the Middle Ages

“Or have we eaten on the insane root/ That takes the reason prisoner?”

− Macbeth (I, iii)